Tyrannical Compliance

- Raimund Laqua

- Jan 29, 2018

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 27, 2024

Companies often consider compliance as a "necessary evil" rather than a "necessary good."

They sometimes feel they are forced to comply with arbitrary rules that have little correlation with the outcomes they are trying to achieve.

This isn't hard to imagine when excessive audits and controls are put in place as a reaction to a serious incident or serious audit findings. This reactive approach makes compliance look more like a tyrant rather than a leader.

Rather than serving as a helpful guide like a GPS, compliance has become an oppressive force for these companies. It now dictates and manipulates their actions, much like a controlling puppeteer.

Why is compliance necessary?

Compliance, at its fundamental level, is about keeping promises to obligations that we have made. These obligations may be in the form of agreements to follow such things as: engineering standards, building codes, traffic laws, quality standards, or internal policies and procedures.

In addition, regulations and standards set a benchmark for normative behaviour. Without them we would all be doing our own thing. While this may have some benefits, it breaks down when we try to work and live together.

As an engineer, I have always had to comply with rules (i.e. requirements) of all kinds such as: laws of physics, mathematical theorems, laws of cybernetics, engineering standards, time and budget constraints, and the list goes on. Professional engineers in Canada (and other parts of the world) are also constrained by law to protect public safety which adds ethical and moral obligations.

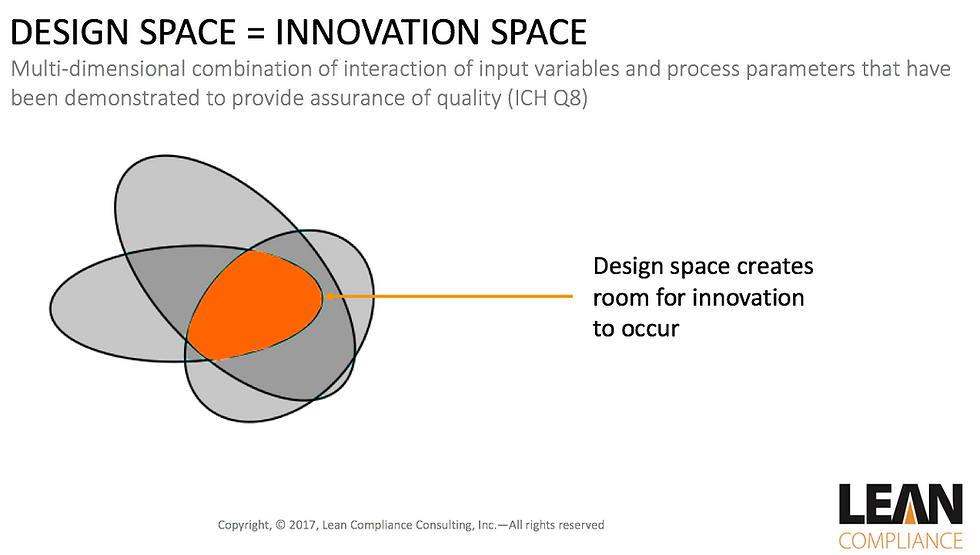

All of these are a form of constraint, and to an engineer these are seen as challenges and not problems. The essence of engineering lies in designing solutions that work within given constraints while planning for unforeseen circumstances to ensure system goals are achieved. Far from stifling innovation, these limitations actually fuel creative thinking.

Compliance with regulations in many ways is no different than an engineer designing a system to meet product or customer requirements. However, what is different is the way in which these are done and therein lies the rub.

We know it's best to design safety and quality into our products, services, and manufacturing. This produces better results than inspecting and auditing for conformance afterwards. The former makes compliance an engineering problem, while the latter makes it a policing and enforcement problem.

When compliance is viewed primarily as a means of imposing rules, it's no wonder many regard it as an unwelcome but unavoidable burden.

When is compliance evil?

We know that too much order (or control) removes autonomy from both individuals and organizations. At some point this loss of autonomy diminishes agency, among other things, resulting in companies only doing the minimum of what is asked of them. Many organizations subject to heavy governmental oversight have, regrettably, experienced this perspective firsthand.

Companies may also not differentiate between conformance to a standard and compliance to a regulatory statute. For example, many view compliance as a tax on productivity and so they want to do the minimum as they do with paying their taxes. This same perspective is often applied to other kinds of obligations. Minimizing taxes is one thing, however, taking this same minimalist approach for safety and quality is another matter and perhaps even unethical.

Sometimes, regulations and standards are not well designed which further contributes to a negative view of compliance. This can be seen with early versions of the quality management standard ISO 9001. When this standard was introduced, it was very prescriptive and subject to much interpretation. Recent changes to this standard have attempted to address some of this by moving to a management-based approach. This affords organizations with a greater degree of autonomy. However, this comes with the requirement that organizations develop their own means (their own rules) by which they will meet their obligations.

With greater autonomy there is also greater responsibility.

This realization is becoming evident to those implementing risk-based approaches in their compliance programs. The lack of prescription, while a good thing, is viewed negatively because it's more difficult to audit. Instead of checking conformance to a prescriptive rule, you need to evaluate performance and effectiveness against targeted goals and objectives.

As a consequence, auditors can no longer tell organizations what to do and neither should they. Each company must figure out for themselves how best to manage risk to prevent defects as well as achieve their quality outcomes.

How compliance can be a leader rather than a tyrant

Organizations should not give up ownership for meeting obligations by blindly following standards and regulations as if these were tyrants. Instead, they should take back responsibility and own their commitments. This involves deciding what strategies are best for their company to meet all their obligations and stay ahead of risk.

And when it comes to safety, security, sustainability, quality or the environment, this requires more than just following rules. It requires leading the organization towards better outcomes.

Finding the right balance that creates enough order without sacrificing too much autonomy is challenging. However, this is precisely the challenge for those accountable for obligations must take for compliance to fulfill it's purpose of protecting and ensuring value creation.